|

| Christmas Tree in Covent Garden, London |

We pick up where we left off yesterday with…

Christmas Cards

|

| The First Christmas Card (click to enlarge) |

Perhaps no Christmas tradition simply popped into existence more suddenly and has changed practically none since doing so than the Christmas card. In 1843, Sir Henry Cole, an English civil servant and inventor, commissioned artist John Callcott Horsley to create an illustration to replace his former practice of writing personal letters to all of his friends bestowing holiday wishes. In true industrial revolution style, his idea was that he could take advantage of the current state of the art in print production (the ability to have something printed was still a novelty: printing previously was only affordable by publishers) and “automate” his well-wishes. While practically none of his other inventions can be remembered, his invention of the Christmas card is enduring.

The instructions of Cole’s commission to Horsley reflect a phenomena that can also be attributed to the Victorians: Christmas charity. Flanking both sides of the color depiction of his family toasting the recipient are scenes of food and clothing being distributed to the poor. The Victorians, perhaps due to their sudden newfound middle-class comforts, extolled concepts of social responsibility, a theme that would be immortalized by a certain author in a certain book we’ll discuss shortly.

Sir Henry’s Christmas cards were a hit. What he didn’t use for himself, he sold for a shilling apiece. The newly introduced penny post (which he helped introduce, opportunistically) made it cost effective for the upper ends of the middle class to buy and send them. A few years later printing costs had fallen such that most of the middle class could buy and send Christmas cards. For the next few decades, Victorian Christmas cards sported hopeful visions of spring, sentimental images of children, and humorous cartoons. Scenes of winter and religious themes would come much later.

Today’s Christmas cards serve an identical purpose to Cole’s original card and come in practically the same form. Sir Henry Cole, by the way, went on to found the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, a veritable temple to the Victorian age. The V&A (as it’s abbreviated) even has one of Cole’s original Christmas cards which this nomadic travel blogging couple tried to view, but alas! we didn’t realize it wasn’t on display and we needed to make reservations to view it.

Sadly, Christmas cards seem to be a dying tradition. Today’s always-in-touch, Internet-instant-communications essentially make Christmas cards anachronistic. But this empty-nest travel couple thinks Christmas cards are a great tradition, a terrific way to pause periodically and go out of our way to let our friends know we’ve thought of them. So we’re doing our part to keep Christmas cards alive.

Moving on to…

Gift-Giving

Before the Victorian era, gift-giving was conducted on New Year’s Day rather than Christmas. The first day of the year was more popular as a holiday than Christmas, and the beginning of a new year seemed the logical time to give your loved ones something new to carry into the new year. As the holiday preference shifted to Christmas and those modest gifts were hung on the tree, the whole gift-giving practice shifted to Christmas, readily associated with the Christian notion of Christ being God’s gift to the world.

Like New Year’s gifts, Christmas gifts tended to be simple and modest: homemade crafts of a practical and useful nature, needlework, clothing, fruits, nuts, and sweets that were not often enjoyed the rest of the year (in other words, they were special, like the one banana my mother got each year in her stocking). Most gift-giving focused on the neediest of the family, the children. Socks and underwear really were a treasured gift at one point (that is after the sweets were consumed and particularly on cold winter nights).

Over time the presents became less practical and weren’t limited to just children. Toys became common, as did games. And as we said yesterday, Victorians loved games. For that matter, they loved all manner of frivolity and celebration, from games to dancing (an early version of polka was THE dance of choice) and–of course–singing.

Christmas Carols and Caroling

No other season, event, or human endeavor of any kind has sparked the creation of more unique songs than Christmas. The word carol, by the way, comes from the French word carole, referring to a type of dance accompanied by singers. Singing and dancing was just what the Victorians loved to do.

Singing has always been associated with worship, so obviously the Victorians didn’t invent the notion of singing a religious song at Christmas. Indeed, Adeste Fidelis is widely believed to be the oldest Christmas carol and dates to 1751. But if you check out this excellent blog, you’ll see two distinct growth spurts in the Christmas carols we are all still familiar with. The first, of course, occurs during the Victorian years of 1830 to 1890, and the second occurs during the middle 20th century.

You’ll also notice that most of the Victorian carols are religious while the 20th century carols are secular. While there were early secular carols, like O Tannenbaum and Deck the Halls, the Victorians seem to greatly prefer carols of a religious theme. I think this is likely because it was the material that composers were willing to create in that era, and perhaps that they loved tying the religious theme of Christmas in with their celebrations. What the Victorians did uniquely was put together small bands of singers to walk around singing carols (i.e., carolers): there would often be a musician (such as a violinist), a few vocalists, and someone to sell sheet music or to collect gifts of sweets or drink, often of wassail, a hot alcoholic cider similar to today’s hot mulled wine still popular in Britain. Hence the carol Here we come a’wassailing.

And finally, singing is a form of…

Story-Telling

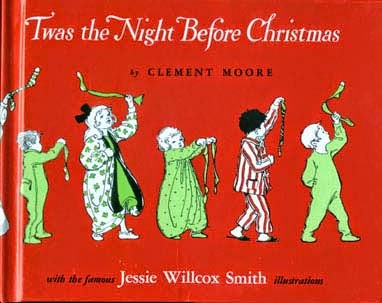

Two stories were created in the Victorian age that did more to define our modern notions of Christmas than anything else. In 1823 a Children’s poem titled “A Visit from Saint Nicholas” was published anonymously in America. By 1837 it had been attributed to one Clement Moore, an American professor of theology and divinity in New York City. This poem is likely the best known, most recognizable of all American poetry. It established the American notion of Santa Claus, largely based on the description of Saint Nicholas by fellow writer Washington Berlin, but Moore blended the stories and traditions of practically every Father Christmas figure from western Europe into his own Santa Claus. The poem, its verse practically perfect and its imagery endearing to children and adults alike, was wildly popular then and still is today.

Only a few years later in 1843, across the ocean, Charles Dickens published the novella “A Christmas Carol”, introducing the world to Ebenezeer Scrooge and the story of his Christmas salvation at the hands of the ghosts of Christmases past, present, and (dreadfully) future. It is one of the most widely known and adapted stories of all time and remains a perennial holiday favorite on the big screen, the small screen, and on the stage to this day. It’s particularly interesting that what inspired Dickens to write the most popular Christmas story of all time was precisely drove the Victorian Christmas revolution: the industrial revolution and its negative effects on society, particularly children.

But lest we get ahead of ourselves, we’ll save the exploration of Dickens’ life to a soon-to-come blog. We hope you’ve enjoyed this two-part blog on how the Victorians defined Christmas as we know it today, and we especially hope it’s helped you get into the holiday spirit, just as the Victorians would have hoped.