Between June 15 when we left on this trip and on December 22 when we step off the Queen Mary in New York, there will be 190 days. Of those 190 days, we’ve had about 22 “driving days”, or days where either of us operated an automobile for any distance. Had we stayed home instead of going on this trip, we would have very likely had 190 driving days out of 190. And we’re pretty normal. We Americans just can’t stay out of our cars.

It’s not entirely our fault. Europeans have a much more complete public transportation infrastructure. Even in the rural “confines” of where we stayed in Nottinghamshire, there are twice hourly trains to the cities of Nottingham to the south and Chesterfield to the north. Even in cities not large enough to warrant an extensive subway system, there are trams and busses. Europeans can get around almost as easily as Americans, but the difference is they get to their destinations having been productive on the way and arriving a bit fresher.

I could have gone this entire 190 days without driving at all. It’s also a fact that, of those 22 driving days, only 4 were on the continent and therefore in a vehicle configured as we Americans are accustomed to (meaning driving station on the left and driving in the right lane). If you didn’t know, continental Europeans drive like we do, but those on the Isles (the UK and Ireland) drive the opposites. I’ve driven so much the last few months from the right side of the car and in the left lane, that it’s become automatic that I approach a car’s “wrong” side to get in and automatically pull into the “wrong” lane. It’s going to be scary to drive with me when we get home.

Some Americans so worry about driving from the “opposites” here in the Isles that they take English driving lessons before they leave. They ride with an instructor in a car with the steering column on the right side on a closed course where they can drive in the left lane. This seems a little extreme to us, and besides, we’ve had enough practicing driving in the Bahamas: as a British Commonwealth country, they too drive in the left lane, but in American hand-me-down cars steering from the left side, so it’s sort of a compromise of Anglo-American driving.

On the continent, as you’d expect, all the posted signs are in the local languages but often have English subtitles. That wasn’t the case–sadly–for us in Portugal. We had to learn a bit of Portuguese rather quickly in some cases. Speeds on the continent are also posted in metric: kilometers per hour. In the Isles it’s a frustrating mix: measurements are still Imperial (good ol’ miles) in the UK and Northern Ireland, but in Ireland–a full blown member of the EU–they’re in kilometers. Most of the time the speeds posted are roughly the same as what we’d have for similar roads in the states, but not so in Ireland: on one tiny country two-lane road we hiked, the posted speed was 80 kilometers per hour. It would be like posting a 50mph speed limit on an uphill alley. We wondered if it were possible to do 80 on that road, but somehow we knew an Irishman or two had indeed accomplished it.

|

| Our Rental – Ford – in Ireland |

Speaking of wild driving, the stereotypes of Italian drivers are true. It actually seems to be the standard for southern Europe, equally applicable in Spain and Turkey. We’ve not been to Greece yet, but we’d expect the drivers to be, well, “Italian” in nature. Driving on the autobahn in Germany is indeed an experience, but one that we enjoyed many years ago, not on this trip. Of all European drivers, the ones most like Americans are the British. Which seems entirely ironic given they drive from the wrong side of the car and on the wrong side of the road.

In the UK, and in Ireland to a somewhat lesser extent, they’re crazy over traffic circles. They’re sometimes called roundabouts. They’re a clever and useful traffic invention to manage intersections without a traffic light. We’re starting to get them in the states, and their advantage of continually moving traffic is obvious. They have them on the continent (the circle around the Arc de Triomphe in Paris is legendary), but they absolutely love them in England. Just up the road from where we’re staying in Nottinghamshire is a small village with no less than 3 traffic circles on the 1/2 mile main drive; two of the circles are barely separated by 20 feet, meaning you exit one and are immediately entering another.

Traffic circles can also accommodate the intersection of more than just 2 roads much more neatly than lights or signs. To that end, traffic circles in the UK can now reach a diameter of a mile, can replace freeway interchanges, and can spin traffic off into many directions. One circle we drove in had 8, perhaps 9, entries and exits. For bigger and busier traffic circles, traffic lights are added, which sort of negates the advantage of continuous movement when you think about it, but with the larger circles, lights become necessary to control the flow of cars entering and moving around the circle. The unfortunate result is that the approaches to the circle for each of those 8 or 9 roads can get seriously backed up while the other 7 or 8 are given access to the circle.

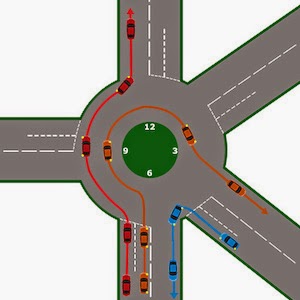

The roundabouts we have in the states being simple compared to some of these, a few words of advice on using them might be in order. On the continent, where they drive “normally”, i.e. from the right side of the car and in the left late (and I mean nothing disparaging to our dear, English friends by that), you always turn right into a traffic circle, the resulting direction within the circle being counterclockwise. On the isles, it’s reversed: you turn left into the circle and the traffic direction is clockwise. Entering a circle you always yield to traffic already in the circle. To put that another way, you always yield to traffic on your left on the continent and you always yield to traffic on your right in the UK and Ireland.

Should you be on a quest for traffic subservience, in theory–though it’s not advisable–you could enter a circle and continually drive in circles forcing all other drivers to yield to you. Please claim to be Canadian if you attempt this.

If the circle is a simple intersection of two roads, the easiest path is obviously the first exit, effectively a right turn on the continent or a left turn in the UK and Ireland. Simply hug the edge of the circle as you enter it. Going “straight through” the intersection will mean skipping one exit, unless you’re crossing the top of a “T”. If you need to skip an exit, be prepared to travel more in the center of the circle versus hugging the edge. And finally, if you need to completely circumnavigate the circle to get to your exit, travel on the inner lanes of the circle and nudge a little more outward with each exit you pass. For those larger, multi-exit circles we mentioned, you might even be directed to specific lanes based on where you want to wind up: pay careful attention to the lane markings. If you miss your exit, you can always run the circle again (waving a Canadian flag), and if you’re forced to exit the circle prematurely you can make a u-turn and try again, hopefully without ping-ponging in and out of the circle errantly.

Finally, a word on DUI’s. In the states we’re accustomed to the 0.08% blood alcohol level as the standard, with a few states varying lower. In most of Europe, including Ireland, it’s a considerably more stringent tolerance of 0.05%. In some countries, like Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Sweden, it’s 0.02%, meaning a good dose of Nyquil will put you at the limit. Should you wish to drive in Romania, the limit is 0.00%–not even trace amounts of alcohol (as in taking a whiff of Nyquil) are permitted. Only the UK and Malta (oddly enough) have an 0.08% limit to match the US.

DUI penalties can also be harsh compared to the states, including months of jail time and tens of thousands of dollars in fines. Unless you want to be forced to extend your visit and drain your bank account, t’s simply not worth the risk.

Tomorrow we conclude our series on life on this side of the pond by discussing a few of the things Europeans have that we envy.