I went to a bull fight in Valencia, Spain this past Saturday. To go wasn’t exactly an easy decision, but I’m glad I did. If for no other reason, I can objectively report to you what I saw.

A little about my nature: I don’t really consider myself an “animal rights person”, but I also don’t care for wonton and cruel killing of animals. I’m a proud omnivore, personally, but I have nothing against vegetarians. I support people’s rights to hunt, though I’ve never personally gone hunting. I can see the argument in support of Spain’s bull fighting as a cultural tradition, but it’s not my personal cultural tradition, and it certainly seems to be a bit anachronistic. All of which, perhaps, justifies my objectivity.

I will say this about the experience: it has changed me, though perhaps not in the way you would expect.

I once beat up a kid for cruelly pummeling a bird to death with rocks. I’m not necessarily proud of the fact, but I was around 13 years old and I was the biggest kid on the block (meaning I got to set the rule: no cruel bird-killing on my block). I cringe at stories of cruelty to dogs and cats, and I sympathize with organizations and governments trying to curb poaching and hunting of elephants and whales. So why am I (comparatively) indifferent to the treatment of bulls in bull fighting?

I spent a fair amount of time in the proximity of farms when I was a kid. My grandmother lived in rural Alabama, and while she was beyond the age of operating a farm, cow pastures surrounded her house. I’ve seen my fair share of cows and bulls, I’ve been close enough to hear them breathing, and I remember tales of people being gored, warnings from family to don’t even think about getting into that pasture. Though having been on the receiving end of the glares of a few of those bulls is more than enough to convince even the biggest kid on his block to stay out of those pastures.

Aside from the presumption that bulls are just downright mean creatures, capable and willing to use those horns to flip a teenage boy twenty feet into the air quicker than you can say “Yee-Haw!”, a major difference between bulls and other animals is that their current, modern existence is owed to thousands of years of domestication by us humans, with the sole purpose being our consumptive pleasure. That makes them distinctly different than wild elephants and whales, as well as from dogs and cats which have been domesticated for companionship rather than as a food source (at least I assume).

So here I will endeavor to dispassionately report to you what I saw that night. But first, I have a spoiler alert for those planning to see their own bull fight one day soon: a bull fight is a fight to the death, and the bull never wins. As my friend Tay pointed out to me on FaceBook when I sought opinions and recommendations on whether I should attend a bull fight, the history of matadors versus bulls is about 1,523,749 to 0. Though to be fair to the bulls, I imagine there have been a few “ties” where the toreadors received some fatal injuries in the ring, but I am certain that didn’t lead to a champagne celebration for the bull.

If you are an animal rights person or someone who might get queasy over accounts of such things, you might want to quickly skip down to the picture of the dashing toreador below.

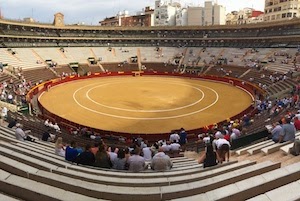

The bull fighting ring is a perfect circle of sand, maybe 100 yards in diameter. Four large entrances to the ring divide it into quarters, and they are large enough for mounted horses to enter the ring; one of the entrances is split into three stalls. Surrounding the ring is a sturdy wooden fence a couple of inches thick. Periodically there are offset “gates”, simple gaps in the fence that are protected by fixed sections of fence that stand inside the ring, the result being that people can enter and exit the ring but large animals like bulls cannot.

There is a festive air about the place, but unlike a circus or baseball game, it is reserved. Spanish people take their bull fighting seriously. I had expected the crowd to be primarily composed of old men, sporting hats like mine, chewing cigars like I wished I had, and talking hurriedly in Spanish while eyeing the ring. Instead I found the audience to be a near-perfect cross section of the Valencian population: young and old, even children, men and women alike. The only demographic I got right was Spanish, but even then, I know I wasn’t the only foreigner, nor the only American.

Before the fight, a uniformed brass band circles the arena playing the kind of tunes you’d expect to hear at a bull fight: heralding trumpets in minor chords as if from a Tijuana Brass album. It is the Posada Doble, another distinct Spanish tradition, for which there is even a regimented dance. They exit the arena and make the climb to the highest point overlooking the ring. They would surprise me with their role in the activities.

To enthusiastic, yet somewhat muted, applause, the entourage of toreadors who are tonight’s entertainment, those on foot with sequined costume and capes as well as those mounted on horse, enter the arena from the large door on the far side from me. They proceed across the ring, raise their hats high, and bow to who I would learn later is the president of the bull fighting league. These are student toreadors, learning the “craft”: basically I attended a minor league bull fighting performance.

After some bending and flexing and as the crowd and the band settles down, the majority of the entourage leaves the ring, leaving only four “assistant” toreadors with distinctive pink capes who stand near those protected gaps in the fence. A man carrying a sign announcing the name of the matador, the principle bull-fighting toreador, appearing next walks to the center of the ring, rotating slowly for the crowd to read. He leaves the ring and another man emerges from one of the three stalls. This man surveys the ring and waits patiently for any straggling arena worker to leave. Once satisfied, he returns back through the entrance, but he leaves the gate open. The stadium is eerily silent.

For what seems an oddly long time, nothing happens. Then, suddenly, a bull emerges into the ring, running at full charge, the crowd cheering him. He skids to a halt in the sand, confused by his new surroundings and the sounds. He snorts, glances around the ring, spots one of the distinctive pink capes, and charges. He is a black, 1-ton animal running at full speed at a man calmly waiving a pink blanket. With uncannily careful timing the toreador ducks behind the fence for protection and the bull rams the fence at full steam, the sound filling the entire arena. The crowd gasps, impressed with the bull’s vitality.

Let me interject here that seeing the bull was a bit of a shock to me. Even given my attitude toward him, I sympathized with the creature. He was going to die, and he was the only living creature in that arena that didn’t know it. He was so full of life, I found myself–despite knowing his fate–wanting to sympathize with him. In my mind, I named him Edward, I have no idea why: don’t they always say to never name a farm animal bound for slaughter, lest you get attached?

The toreadors took turns waving their pink capes around, taunting Edward the bull to run their way, then to the next. They were tiring him, wearing him down. As full of life and energy as he was, it was effective. Then, the far door opens, and to the band’s fanfare a mounted toreador enters the ring carrying a spear. This was the part I had no idea about: before this night I thought a bull fight was a mano-a-bull, 1-on-1 fight. That there was more than one toreador I had come to accept, but that there was a mounted toreador with a spear seemed unfair at first. But I would learn that this step in the process was critical in hurrying the process along: otherwise, the bull’s inevitable fate would take hours to bring about.

The tired bull is corralled by the toreadors on foot, now joined by the match’s chief toreador–the matador–in resplendent sequined attire with distinctive and colorful stockings. As the band plays on, they corral the bull, spinning and charging at their capes, toward the horse. Then he charges the horse. Though the horse wears an armor of sorts, the momentum of the animal pushes the horse back, sometimes lifting him in the air, but–with years of training and practice–the horse stands firm as the mounted toreador stabs the bull from above with the spear. He is swift and powerful, pushing hard with all his weight so that the spear wounds the bull deeply and decisively. I imagine this wound alone is fatal. If the spear slips or the blow is glancing, he quickly tries again. Sometimes he is refreshed with a new spear, but always the result is the same: the bull is now seriously injured.

The toreadors back away, giving the bull time to recover from the initial shock. The mounted toreador exits the ring. The band plays a song that I would soon equate with inevitability. The bull is dying and his sides are wet with blood, yet he makes a charge at one of the toreadors. Invariably he stumbles, the sudden loss of blood disorienting him.

The toreadors back away, leaving the featured matador with his red cape in the prominent position of taunting the bull. Rallying somewhat, Edward the bull charges him, always pursuing the bright red cape instead of the man just to its left or right. The crowd shouts Ole! to the more artful, close-quarters passes. Meanwhile, one of the toreadros returns carrying only a pair of red and yellow banded stiletto-style knives about a yard long called banderillas. The others retreat and the bull spots the toreador with the banderillas, who adopts something of a Kung-Fu swan pose, taunting the bull to rush him, and as he does, the toreador leaps and stabs him just behind the shoulders while avoiding being gored. If the toreador is successful, the banderillas stick and the crowd cheers approval; if he is unsuccessful, he endures the jaunts and jeers of the unforgiving crowd. It seems the crowd prefers clean and decisive wounds.

The animal is wounded by three pairs of banderillas, the red and yellow sticks dangling from the animal’s shoulder, now bleeding profusely. The music starts up again–another verse of the Posada Doble–and now it’s just the bull and the matador. The matador strikes outlandish poses and waves the red cape and shouts to taunt the bull. The bull continues to rush the cape and the two of them wind up in such close quarters that the animal could gore the matador with a flick of his head, but Edward the bull is intent instead on the cape. The bull sometimes stumbles, sometimes even catches his horns in the sand, but he continues to get up. And sometimes the bull gets the best of the matador, knocking him to the ground with a sideways swing of his massive head, or flicking him up into the air with those deadly horns. But the bull’s tongue is wagging, he’s drooling, and if he stands in one place for very long, his blood pools in the sand.

This is the mano-a-bull, 1-on-1 scene we who are uninitiated into bull fighting expect to see. With each rush, though they are becoming less and less frequent, the crowd cheers: but are they cheering for the bull or the matador? They watch intently, the smell of cigar smoke fills the arena, and the band’s music fades. A few people stand and give a thumbs-down sign, reminiscent of a gladiator fight. It’s time for Edward to be put down.

The matador is brought a sword. Using the sword at first to hold the red cape up, he renews his efforts to wear the bull down. Sometimes the bull becomes invigorated, his charges more energetic. But this is always short lived. As the bull stands eying the matador, panting, swaying, the matador points the sword at the animal. The music dies down and the crowd shushes one another so that the arena is deadly quiet. It is man that charges animal now. If he is successful, the sword is buried in the animal’s flesh behind the shoulders. If he is not, the crowd is again unforgiving. That sword is replaced with a stronger sword and there is another charge. There is perhaps a third, until the animal becomes lethargic, swoons, and stumbles.

Quickly the matador approaches the animal, places a sword just behind his skull, and with a quick thrust ends the animal’s misery.

There is a flurry of activity. Workers and the toreadors enter the arena floor and affix a chain to Edward the bull’s horns. A team of two horses enters rom the opposite entrance. The matador is nowhere to be seen as the bull is attached to the horses and dragged from the ring. The crowd applauds, obviously for the bull. Only once the animal has been pulled from the arena does the matador return to applause, and if the crowd approves of his performance, enthusiastic cheers.

As I said earlier, the experience of the bull fight changed me, yet not in the way you’d expect. I remain ambivalent over the political correctness of bull fighting, though I must admit I think it would be a loss to Spain if it were ever banned. I am changed in that I have seen that bull fighting is indeed a cultural event for the Spanish, and if it is to become part of the history books, well then that must be a Spanish decision.

As with so many experiences we travelers purposefully seek out, I learned a great many things with this experience. I expected it to be a much more gory, protracted affair than it was. I was surprised at the respect of the crowd for the bull. And I was pleased to learn that the animals were immediately cleaned and prepared for market; I guess I should have known that no Spaniard in their right mind would let a ton of beef go to waste.

Perhaps the biggest appreciation I am taking away from this experience is that of bull fighting as a sport. I tend to agree with Hemingway’s assertion that, “There are only three sports: bull fighting, motor racing, and mountaineering; all the rest are merely games.” If NASCAR and golf can be called sports, certainly having to kill a 2,000 pound angry animal with your bare hands is a sport, even if it is a team event.

Still, I can’t help but wonder how this tradition got started. Perhaps one time, long ago on a farm in Spain, a 13 year old boy, egged on by his friends, didn’t heed his family’s advice and he jumped into a dusty pasture armed only with a pair of banderillas.